Non-academic research essay, published 9th February 2024

Introduction & Hypothesis

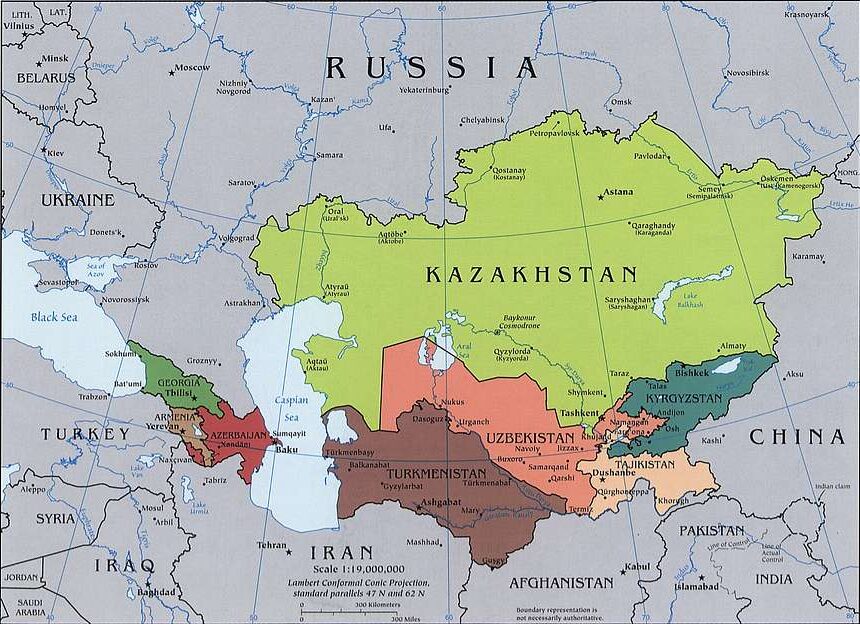

Throughout history, the inland region of Central Asia has been a source of great intrigue and temptation to the world around it. As outlined by historian Hina Khan, Central Asia has played an important role as a land which outside powers have sought to win control at different points in history. Firstly came the Mongol Empire from the east, then the British and the Russians looking to expand their influence from the north and the south respectively, and now Russia, the West and China all looking to win over a reinvigorated region. Historically, the importance that Central Asia has played in the foreign policies of numerous major empires was due to its position as a crossroads which connected different civilisations through trade, becoming famously known by the ‘Silk Road’. This put Central Asia at the heart of the historical world.

During the twentieth century, however, Central Asia was regarded as little more than a straggler in the Soviet Union – an economic dustbowl in a rapidly modernising world. Fortunes though have been changed completely thanks to the discovery and exploitation of large reserves of oil and natural gas, a trove of treasure in an era of increasing instability. Oil and gas production in Central Asia has once again invited the gaze of the world’s strongest nations. With mega-sized superpowers such as the U.S. and China burning through more fuel than they have, and prices fluctuating in an era of political turmoil, a bank of reliable energy output is becoming an increasingly valuable proposition that cannot be passed up. The importance of Central Asia, therefore, is once again coming to the forefront in geopolitics.

To understand the important role Central Asia is taking on today, and why outside powers have taken such careful consideration of the region, an understanding of Central Asia’s place in the world historically is a fruitful source of knowledge. This is because the situation that Central Asia has found itself in in recent years – as a subject of competition for rival powers, reflects its experience in the nineteenth century, when it was fiercely competed over by the British and Russian Empire.

The ‘Great Game’, as it has come to be known, saw the British Empire and the Russian Empire battle for control of Central Asia due to the importance of its trading routes, but more importantly over the fear of the other side taking control of them, and therefore tipping the scales between the two dominant empires in Eurasia. This event provides a unique historical comparison to Central Asia today; as whilst it was partially defined by military conquest and territorial expansions from both sides, it was more so defined by a number of political, economic and cultural strategies more resonant of the post-colonial era today. In the era of empires, it was normal for a powerful nation to conquer and subjugate a much smaller state, and it could be seen as a surprise that these more brute tactics were not employed immediately in the race for control over Central Asia. Yet what transpired over the nineteenth century was a political chess game, as both powers sought to expand their diplomatic and economic influence over the region.

The reason for these less overt forms of expansionism may have been that the arid and mountainous terrain provided many challenges for an invading army, and that the vast stretches of land populated by nomadic tribes and disparate communities were undesirable to rule over. Either way, these strategies were highly unusual for the time, and are better categorised with the strategies being used by powerful nations who have continued to expand their influence in the post-colonial era. After the collapse of many major empires, and the collective memory of two world wars, the conquest of a sovereign state has become seen as beyond reproach in a world of cooperation and international law. Powerful states have therefore turned to more ‘ethical’ ways of expanding their influence – methods which make up a spectrum including proxy wars, backing political factions, economic expansion and trade, diplomatic strength and cultural influence, often defined as ‘neocolonialism’. The concept of ‘neocolonialism’ provides a framework through which to study how the emerging superpower rivalry over Central Asia is unravelling. Studying the actions of the past and present; and the similarities between them develops an understanding of the potentially surprising role that Central Asia has played in shaping the modern world, and how its politics have also been shaped by this dynamic, turning Central Asia into a truly transnational and global part of the world.

The ‘neocolonial’ actions that were first exhibited in the nineteenth century show the development of new strategies for spreading and consolidating influence in a truly globalised modern era of history. Central Asia’s position at the center of the world’s major powers and their competing interests has played a huge role in constructing these strategies, as expansive nations have sought to muscle their dominance in the region, but have also had to more skillfully promote their own interests over those of their rivals. The dynamics that have resulted from this have come to shape modern geopolitics, bringing an end to the long era of pillage and loot, and ushering in an era of mutual benefit and political cooperation, albeit dominated by the powerful. Not only this, but Central Asia has been transformed by its global connections, developing its own foreign policy autonomy and becoming a truly powerful actor on the global stage.

Entering the Modern Era: Central Asia as a Central Periphery

The Great Game emerged in the nineteenth century as the two great powers of the time, Britain and Russia, clashed over their desire for global supremacy. Having successfully charged East into the wilderness lands of Northern Asia and Siberia, and soon after crossing over to North America, the Russians were looking to build on the rapid expansion of their empire by pushing into the steppes that would give them access to the riches of the East. On the other side, the British Empire, having become a juggernaut through its conquest of India and its dominance over the seas, was playing a more defensive game, trying to protect its interests in the East from Russia’s newfound ambition. In the late eighteenth century, Central Asia became the barrier which separated these two empires. To the south of Russia were the loosely organised Kazakh hordes that inhabited the steppes, followed by the Khiva, Bukhara and Kokand Khanates that ruled the Islamic heart of Central Asia. To the north of British India stood the Kashmiri Mountains and the Emirate of Afghanistan, founded in 1823. This would be the stage of a century-long ‘game’ of political manoeuvring between the great powers.

Competition over Central Asia started in the periphery areas. Diplomatic relations between the Russian Empire and the Kazakh tribes had been active since the 16th century, but in the eighteenth century the Russians sought out the opportunity to build trade relations, developing settlements in the south of their empire which became trading hubs for Central Asian merchants. The Kazakhs also became drawn to the Russian sphere of influence through the need for military protection, fearing invasion from the Junghar tribe and the Chinese Manchus from the east. Using these factors, the Russian Empire convinced two Kazakh hordes to accept nominal Russian sovereignty in the 1730s. The Russians quickly utilised this by building new fortifications and sending expeditions further south. Their ambition to conquer Central Asia had taken root.

Meanwhile, as the British established control of India in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, the expansion of Russia into Central Asia came into direct conflict with their interests. British foreign policy in the nineteenth century therefore became increasingly focused on the containment of this perceived threat. The approach that Britain decided on was to use Afghanistan as a buffer state. Britain took a diplomatic approach, sending political agents to convince the Afghan leadership of an alliance with Britain against Russia, and supporting leaders who were friendly to their interests through arms and funding.

The failure of Britain’s diplomatic ventures in creating a lasting alliance, however, led to two British invasions of Afghanistan. The first largely failed to achieve its objectives, but the second was more successful, as the British managed to march on the capital, Kabul. Even after taking Kabul in the second war, however, Britain still did not bring Afghanistan into its empire. Instead it forced Afghanistan into its orbit with a peace treaty that gave Britain some of Afghanistan’s northeastern territories, and agreed that the Afghans would allow British control of their foreign policy. Britain’s invasions resulted from deteriorating diplomatic relations with Afghanistan, but were motivated by fears of Russian expansionism towards India. In the 19th century Russia became increasingly bold in conquering territories. The Middle Kazakh Horde had re-declared independence after accepting Russian protection, but in 1822 the Russian’s drafted a Kazakh code, making the whole territory part of the Russian empire. By 1847 they had conquered the Greater Horde in the south. Initial military expeditions into the Khanates had failed, but they were eventually defeated one by one and brought under Russian control. Now on the border with Afghanistan, the Russian lust for land alarmed the British, who saw them as uncivilised brutes intent on plundering foreign lands. British anxiety reached its height in the Great Game.

Stuck between Britain and Russia, the Afghan state was faced with an unprecedented foreign policy situation in its short history, knowing that allying too closely with one side could spark a war between the two great powers. Under the leadership of Sher Ali Khan, who solidified his control over Afghanistan in 1868, the country pursued a pragmatic foreign policy of neutrality, promoting diplomatic relations with both sides. Neutrality, however, could not override the fact that Britain was the largest power in the region, and therefore an important focus of Sher Ali Khan’s foreign policy. Britain backed Sher Ali Khan to come to power, and supported him with a significant amount of financial aid. Sher Ali Khan wanted a treaty with the British assuring that Britain would help keep him in place as ruler and provide him with a fixed income. Britain refused to commit to these requests, but Sher Ali Khan remained unfettered in looking to better relations with Britain. He adopted the British Uniform, made Westernising reforms, and sought to modernise his army with artillery based upon a number of howitzers the British had sent to him.

In the end, however, it was the British who he would end up losing the faith of, as they were dissatisfied with his neutral stance towards Russia, despite their failure to satisfy the Afghan’s demands. The Second Anglo-Afghan war broke out over Sher Ali Khan’s refusal to commit to one side, yet the diplomatic pragmatism and foreign policy neutrality became the historical precedent for Central Asian leaders when confronted with the competing interests of outside powers. A similar approach was taken by Ablai Khan, the leader of the Middle Kazakh horde between 1771 and 1781. Dealing with threats from the Chinese and the Dzungar tribes from the East, and the pervasive influence of the Russian Empire, Ablai Khan employed a multi-vector policy, using diplomacy to build up relations with all sides to protect the horde’s territorial integrity. He was adept at playing different powers off of eachother, utilising the deterioration of relations between Russia and China. When the Kazakhs had to fight on the defensive in the Kazakh-Qing Wars, he brought weapons from the Russians and appealed to them for protection, but when the Kazakhs launched attacks on forward Russian military fortifications, he paved out stronger relations with the Chinese. People like Sher Ali Khan and Albai Khan would become an example to future leaders, providing a framework for dealing with multiple untrustworthy actors at once. In a modern history of neocolonial advances into the region, Central Asian politics would become defined by a pragmatic and self-serving friendliness towards the outside world, combined with a wariness of ulterior motives.

The Oil Era: Central Asia’s Return to the Global Stage

After a long period under Russian domination beginning in the late nineteenth century and concluding with the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and the collapse of the Soviet Union, Central Asia has once again become the focus of a great political battle between the world’s major powers. This time, the now independent Central Asian states have become a lucrative market for much-needed oil and gas in an increasingly volatile world. Furthermore, with the rise of global extremism and conflict in the Muslim world, Central Asia has taken on a strategic importance in geopolitics, with Afghanistan becoming a focal point after 9/11 and the War on Terrorism. As a result, Central Asia has become a battleground for the underlying competition of interests between the West, China and Russia. After over a century of subordination to Russian and Soviet rule, only defied by Afghanistan and their resistance in the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, the position that Central Asia has found itself in in the post-Cold War order is a complete reversal from the position of weakness it found itself in just decades prior. Central Asia had already had its golden era – with the prosperity of the Silk Road and the Islamic renaissance of Mediaeval times, but this is potentially its second golden era – the oil era.

The breakup of the Soviet Union and independence of the Central Asian lands of Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan started a scramble for resources as large oil and gas reserves entered the global market, as well as the opportunity for these countries to open up to a new world of trade, promising personal riches for the political elite of these countries. The so-called ‘oil diplomacy’ that has developed out of this has come to massively define post-Soviet experiences of Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan, the two nations with control over many of these precious resources along the Caspian Sea. These nations have had to juggle the competing interests of Russia, China and the West, who have all looked towards the region for its energy security.

For Russia, securing the flow of oil from Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan is a matter of consolidating its power in its own backyard after the breakup of the Soviet Union, which it sees as its natural right. To this end, they have had to contend with the newly developed interest of a triumphant West, looking to explore the ‘New World’ opened up by the Soviet breakup. Western companies began to take up stakes in the oil industry, and European nations, backed by the United States, began considering proposals for new pipelines to be built. The problem faced by the West was that the Central Asian states needed to send oil and gas through Russia to reach Europe, giving Russia leverage over relations between Europe and Central Asia. To counter this, ambitious yet concrete proposals were discussed between both sides to build the ‘Trans-Caspian Pipeline’ was first proposed in the late 1990s, which would transport oil under the Caspian and through the Caucasian mountains into Europe, and became a constant theme of European-Central Asian relations.

Russia saw this as a threat to their dominance in the region, and responded by strengthening economic ties with Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan. This led to deals being signed on the update on existing pipelines through Russia, effectively killing the Trans-Caspian pipeline. ‘Pipeline diplomacy’, as it has been referred to, has become a key point of contention in the region, but is not the only area where competing powers have clashed. Western attempts to export ideas of civil rights and democracy to the region, such as through the integration of Central Asian countries into the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), has been met with Russia’s own moves to institutionalise its political dominance over the region, with the CSTO binding the Central Asian countries to a Russian-centric military alliance, and the Shanghai Treaty, dominated by Russia and China, agreeing on a number of areas of security, trade and cooperation. Russia has also played up rhetoric about the West seeking to impose its ideology on the region through ‘Colour Revolutions’ and the influence of non-governmental organisations, seeking to break off new areas of cooperation between Western and Central Asian countries, and pushed hard for Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan to end their lease of air bases to the United States, which were used to support military operations in Afghanistan.

Despite these many areas of competing interest between Russia and the West over the years, it is China who likely has the most to gain from the region. China first began to involve itself in Central Asia with the dealings of Chinese companies, who began to take over Kazakh oil companies and build up control of significant portions of its oil production. This was coordinated with quickly successful deals to construct both the Central Asia-China Gas Pipeline and the Kazakhstan-China oil pipeline in the mid-2000s. China’s march into Central Asia has been unstoppable – but more specifically inevitable, as an enormous power adjacent to the region and highly important in the foreign policy calculations of the Central Asian states, and a key global ally of Russia. In 2023, new ground was broken with the first China-Central Asia Summit being held, at which a number of agreements were struck on financial assistance, trade and national security. The meeting signalled a shift in focus from Central Asian countries towards China, with further business deals being struck since the summit, and the nations have agreed to hold a new summit every two years.

The inevitability of China’s growth as the dominant power in Central Asia didn’t stop it, however, from unsettling the delicate balance of interests in the region. Relations between Russia and China, friends on the global stage due to their shared desire to undermine Western global dominance, have been strained by their competing interests closer to home. Russia in the post-Soviet era has been faced with the creeping reality that China has overtaken it as a major power, and is beginning to dominate relations both politically and economically. This has complicated what initially seemed like it would be a friendship between China and Russia, and has made Russia inherently suspicious and anxious of Chinese expansionism, particularly in Central Asia. Russia’s approach to Central Asia in response has focused on trying to build up a relationship of dependency, undermining Chinese influence without taking it head on. Taking advantage of the fact that Central Asian countries are exporting so much of their energy that they are falling short of their domestic requirements, Russia is now promoting the export of its own gas to Central Asia. It has also proposed the creation of a Gas Union with Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, which would give Russia access to pipelines into China, and would pave the way for Russian companies to take control of infrastructure projects in the region.

Facing these external pressures on their own national sovereignty, the leaders of the nations of Central Asia have, again, in continuity with history, turned towards a policy of neutral diplomacy, trying to build good relations with different actors for their own benefit. The skilled diplomacy of historical leaders from the region has been emulated by Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, one of the architects of Kazakh foreign policy; and current president of Kazakhstan. Under his guidance, Kazakhstan developed a multivector policy, repositioning them towards the West and building a close relationship with China whilst also maintaining the trust of Russia. Under former President Nazarbayev, however, this multivector policy was not fully realised, as Kazakhstan remained dictatorial, too much like the system of cronyism in Russia to build a close relationship with the West.

Tokayev has advanced Kazakhstan’s multivector policy, looking to improve Kazakhstan’s image worldwide by bringing in democratising reforms and taking a stronger position against Russia, particularly after the invasion of Ukraine. Meanwhile, he has sought to solidify China as Kazakhstan’s closest partner, making diplomatic overtures to the Chinese and looking to build economic cooperation with them over Russia. Whilst doing all this in just a matter of a few years as President, Tokayev has also managed to maintain a good relationship with Russia, using Kazakhstan’s position of importance in Russia’s orbit to continue meeting with Putin despite his moves against Russian domination in the region. For a skilled foreign policy operator like Tokayev, the scramble for Central Asia’s resources presented an opportunity to better off Kazakhstan’s position in global affairs and to bring about more prosperity for the country, using diplomacy to play competing powers off of eachother and better the rewards Kazakhstan gets from its position of resourcefulness.

Central Asia has once again become a central part of our political world. Even today, when the urge to combat climate change has taken on such a great importance globally, the need for secure supplies of oil and gas remains a high priority for countries in an increasingly volatile world. Central Asia is also at the centre of the need to balance global relations after the increased tensions caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and has become an increasingly desirable trading route between the Western world and the Eastern world that bypasses Russia. A highly-publicised visit by the then British Foreign Minister David Cameron to Central Asia typified the growing importance of the region in global affairs, signalling anxieties about China’s increasing hegemony, and showing that some in the West still recognise the significance of the region in global relations going forward. Going forward, Central Asian relations will be a crucial foreign policy calculation for all major powers.

Conclusion: At the Center of the Modern World

Central Asia may be a relatively peripheral part of the world in the minds of many, but over the past few centuries, it has taken on an increasingly central importance in geopolitics. By comparing Central Asia’s global importance in the eighteenth and nineteenth century to the post-Cold War era, the effect that Central Asia’s centrality has had on modern colonialism is illustrated clearly. Colonialism in the age of exploration was defined by an uncompromising theft and plunder, in which powerful nations took what they wanted and made it their own. In the modern period, however, the development of political institutions and states, as well as multi-power competition for land and resources, began to change the nature of colonial actions. Nowhere was this change more clear than in Central Asia, where the Great Game brought the greatest nations of the world into contact with much smaller nations, exerting their influence by building political and economic dominance.

The reluctance to turn to military conquest in Central Asia raises the question of why this region was treated in such a unique way. A possible answer is that the largely barren steppes of an uncharted and inhospitable region may have proved undesirable to conquer and even less desirable to rule over. In the 21st century, the use of neo colonial approaches has largely been driven by an ethical rejection of blatant conquest and domination of other nations, but is also due to a lack of knowledge and expertise of these faraway lands, which are seen as better left in the hands of local elites, so long as those local elites prove to be loyal allies. Even after Russia took over much of the region in the nineteenth century, it delegated a uniquely high amount of autonomy to the territories, and under the Soviet Union the newly formed states had their own governments.

The evolution of colonial approaches in the modern era, of which Central Asia has been such a big driver, has led to powerful nations taking a spectrum approach to expanding their influence. This means that rather than just focusing on military conquest, a range of economic, social, cultural and political factors are exploited. This ‘spectrum’ of factors can be seen evolving in the colonial competition over Central Asia. For example, the political agents first employed by the British to improve diplomatic relationships with Afghanistan’s leaders were precursors to the ambassadors and diplomats used to strengthen diplomatic relations between nations today. The nominal status given by Russia to the Kazakh hordes to protect from outside threats is now more subtly resembled by military alliances such as the CSTO and the STO. Also the conditional support given by Britain towards friendly leaders in Afghanistan, particularly Sher Ali Khan, is mirrored by the support given by the U.S. in the Tulip Revolution in Kyrgyzstan.

The scramble over Central Asia in the twenty-first century has brought forward new neocolonial norms, ways in which the major powers are able to spread their influence whilst being able to wash their hands of history’s more bloody chapters. The emphasis on economic cooperation and diplomatic formalities mark a new period of productive relations in global affairs, but make no mistake, the balance remains very much tipped in the favour of a handful of nations. These imbalanced relationships have led to economic and political dependency between Central Asia and outside influences, a relationship which has led to some academics describing the states of Central Asia as ‘rentier states’. The concept of the ‘rentier state’ has been applied to Central Asian governments who have become dependent on their energy exports to more powerful nations, which those in charge have benefited from both politically and economically. It is therefore, as suggested, vital to the interests of Central Asian leaders to maintain good relations with certain foreign allies, indebting these nations to the will of their post-colonial ‘rulers’.

This interpretation paints the Central Asia of the post-Cold War era as very limited in its autonomy, under the grasp of allies whom they depend on for their economic and political stability. The evidence presented, however, refutes the notion that Central Asia is made up of ‘rentier states’ dependent on the support of global allies, as it shows a flexibility in Central Asian politics to court strong alliances with multiple actors and play their interests against each other. This flexibility has further increased in the twenty-first century, with political leaders devising foreign policy strategies which aim to bring about geopolitical strength and economic prosperity to their homelands. The fact that Central Asia has become such a focal point of China’s foreign policy, an area of anxiety for Russia, whilst also continuing to court the West at a time when its interests have become tied up in Ukraine and the Middle East, shows the influence that the region has over international relations and the balance of power.

Central Asia is such an important region of discussion and study as it has once again become a critical crossroads in great power politics, proving its centrality in global affairs over time. Even as the world tries to move on from traditional energy sources towards a sustainable world, sources such as oil and gas are still needed for energy security and the increasing demands of a growing population. Central Asia remains therefore a key to global dominance and strength, shaping the foreign policy of some of the world’s most powerful actors, whilst also being fundamentally shaped by its truly global existence. No doubt, the future role that Central Asia will play will continue to have a big impact on geopolitical dynamics, particularly with the increasing tension between the West and its Eastern rivals, which Central Asia finds itself in the middle of. Its study is now of a pressing urgency in our understanding of geopolitics.

Leave a Reply